Over lunch and later, while hiking, I thought about the forest and the farms of the Finger Lakes that I had seen and how generations of people had been supported by foods produced by this land. Devising a cuisine for this place, giving full expression as a set of tastes, seemed like a good idea. After all, almost any local cuisine would be an improvement on the current food system that burns corn for home heat, runs on huge quantities of hydrocarbons and incorporates petroleum distillates into our food.

Our technology allows us to transport goods and communicate information in a way that increasingly homogenizes the world’s food and diet by making all edible things seem equally available. A supermarket in our area displays foodstuffs raised in the southern hemisphere and transported and stored in specialized environments, so that we can enjoy our favorite foods no matter what the season, so long as we can pay for the ingredients. Helpfully, the market posts recipes for unfamiliar foods that can be torn off at the same time that the foods are being bagged and weighed for purchase.

On another hand, our preferences for certain kinds of food are durable. Ethnic foodways are some cultural components that last best and survive longest in “the melting pot.” When language, clothing, gesture and most other components of lifestyle have become Americanized, food preferences linger on.

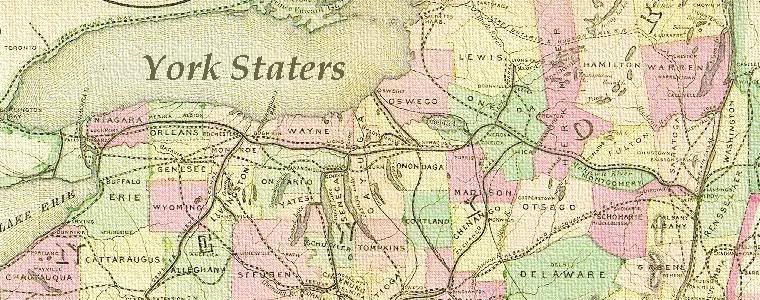

As far as I know, no one in this particular corner of the melting pot called the Finger Lakes (roughly a 14 county area of 8,000 square miles around 11 lakes in west-central New York State) has considered what would constitute our “regional cuisine,” so we are free to imagine. Before a Finger Lakes cuisine can even be approached, there are practical concerns and questions that require some tentative answers.

The questions deal with the availability of transported foods, the season of the year, how much theory versus how much practice will be involved, a distinction between native and imported crops (and native to which regions), and the fidelity to/blending of other existing regional cuisines and ethnic diets. A regional cuisine predictably favors the native crops of the region over transported foods, while keeping the door open for others; addresses seasonal variability; offers both theoretical perspectives and practical suggestions; and avoids simply importing other ethnic foodways to fill in our own gap. In addition, it would be productive to ask what this cuisine is for and to provide answers that emphasize the various roles of food to give comfort, pleasure, and promote health.

The Finger Lakes region is favored with excellent soils and a good growing climate, hard as that may be to believe in the depths of January. We receive something like a yard of precipitation per year and more than half falls during the growing season. Our soils, a mixture of sand, silt, and clay particles left by glacial action, were formed and made rich by ten thousand years of forests and, where deep and flat enough, will grow anything not requiring tropic heat.

The Finger Lakes region supported people who ate well prior to the arrival of European fur traders and missionaries. These earliest people called themselves Ongweh Howeh, or real people, and ate a wide variety of foods provided by the local landscape. Like many other cultures, they devised recipes that turned the potential uniformity of a few basic foodstuffs into a diversity of tastes, a cuisine, as our French cousins would say. The word cuisine’s own history relates to the Latin coquina, for things pertaining to the kitchen and cookery and undoubtedly is rooted in role of the Roman household gods, their lares and penates.

Archaeological investigations indicate that people living in the Finger Lakes for thousands of years hunted and gathered plants and animals for their sustenance. They ate birds such as ducks, geese, turkeys and grouse; larger animals like white-tailed deer, beaver and bear, squirrels, possums and raccoons; and turtles and fish from the streams and lakes. They gathered the roots of plants like Jerusalem artichokes, leeks, and cat-tails; ate greens from plants now considered common weeds such as milkweed, cowslips and lamb’s-quarters; gathered plums, elderberries, strawberries, and black raspberries; used acorns, walnuts, chestnuts, sunflower seeds and hickory nuts for their meat and oil; and tapped the maple trees for their sugary sap.

The activities of these hunters and gatherers slowly changed the environment in which they lived by favoring certain plants and animals for their usefulness and discouraging others. The dividing line between hunting/gathering and farming is not as definite as you might think at first. If you saw that white-tailed deer were attracted to openings in the woods, wouldn’t you set some fires to create and maintain these openings? It would make your hunting that much easier if you could draw these animals closer by offering good browse. Likewise, if you gathered wild plants and prepared them to eat in your home, wouldn’t the seeds of these plants tend to fall in your yard? As these plants proliferated nearby where you could observe their progress, wouldn’t you notice that some were larger, stronger and produced more of what you wanted in greenery, seeds, fruits or roots? Wouldn’t you select seeds and cuttings from these better plants to re-plant near your home in order to have good things nearer at hand? The domestication of crop plants begins with observation and selection. The cultivation of domestic crops begins with altering the environment to create conditions favorable to their growth. A domesticated plant or animal is nothing other than a wild animal or plant so altered in its relationship with humans that it begins to require human intervention and management.

About a thousand years ago, and five hundred years before the first white visitors or colonists arrived, the Ongweh Howeh received a gift that would change their lives. Whether the gift was brought by migrating groups of people (probably coming north and east along the Allegheny River), or was brought by a long, well-established systems of trade, or was taken in the process of raiding neighboring people, it consisted of a few basic agricultural plants and information needed to successfully cultivate them: squash, followed by corn, and finally beans. Women, whose previous role had entailed preparing the gathered foodstuffs and perhaps nurturing early domesticates, found themselves in charge of the gardens. Men contributed to the gardens by clearing land and processing the harvest but remained primarily hunters, even traveling away from home and village for months to follow the food animals.

Whatever the origin and the transmission of the original seeds, they were also attended by sufficiently detailed cultivation instructions to assure their success. The Ongweh Howeh learned that land would have to be cleared for crops to prosper, that wood ash from the burned trees and the land‘s natural fertility would yield good crops for as long as a generation, and that movement to new villages and fields would be necessary to continue gardening beyond that time. They learned that corn, beans and squash would benefit from being planted together in mounded soil and would grow better if weeds were kept away from the food plants, requiring cultivation with hoes.

A regional cuisine for the Finger Lakes is necessarily grounded in this deep agricultural history and in one Native American word: succotash. Like many words scattered over our landscape, succotash originated in the east (the Narragansett coined the word misisckquatash for an ear of corn) and migrated west where it came to be applied to any dish that contained both cooked corn and beans. The Iroquois, as the Ongweh Howeh came to be called by others, had many variations on this dish but called succotash ogosase. A Seneca recipe gathered by Phyllis Williams Bardeau in Iroquois Woodland Favorites (2005) requires “6 ears green corn, 1 pint shelled beans, ¼ cup diced fried salt pork, and salt/pepper. Cut kernels from cobs and scrape off the milk. Place corn in a pot, add the shelled beans, diced salt pork and seasonings. Add water to almost cover (ewowe’sah). Stir frequently (da’ja’ne’) to keep from scorching. Cook for about ½ hour.” Archaeologist Arthur Parker’s Iroquois Uses of Maize (1910) specified that both sweet corn and Tuscarora-variety corn in the “green corn” stage were used, and Tuscarora Dorothy Crouse contributed a very similar recipe to Iroquois Indian Recipes (1978). Ethnologist F.W. Waugh’s Iroquois Foods and Food Preparation (1916) adds several details to the process: the corn was pounded to express its “milk” before boiling, half of a deer’s jawbone was the traditional corn-scraping tool, and maple syrup might be added for taste.

Succotash can be wonderful or awful. It is not a dish that cans well, but it has been canned, overcooked and piled on a plate of meat and potatoes in a way that is not encouraging. Usually, the canned beans are lima beans, a more southern bean than those raised in the Finger Lakes. But who would judge a food by its canned version? Remember that canning’s short history dates from Napoleon’s desire to fuel a huge army a long way from home in inhospitable climes.

We are not an army. We are close to home, our earth is not blackened, and at certain times of year when both the corn and beans are ripe, real succotash becomes a possibility. The absolute necessity for fresh ingredients means that real succotash can only occur for two and a half months of the year, between mid-July and early October. Break open the pods, shell the immature beans into a sauce pan and cook lightly in water enough to cover. Lima beans are okay, but almost any bean picked short of maturity can be a shell-bean. Shell-beans are partly mature beans in which the pod has not begun to harden and the beans have not developed their final, hard coat. Some Iroquois recipes call for “cranberry-style” beans, big fat ones. Take a sharp knife and score the corn kernels along their rows. Then hold the ear against a plate and scrape off the corn kernels. Go as deep as you can on the cob (to get the ‘milk’ as Bardeau calls it) and put the kernels into the sauce pan with the half-cooked beans. Some prefer younger corn for greater sweetness, but others like the texture of fully mature kernels. All the authors specify “green corn” for succotash, an important cultural distinction to the Iroquois who celebrate the appearance of that stage of corn development in late July or early August. In our time, sweet corn is corn that is delayed in the “green corn” stage of development, staying sweeter longer. Add some butter (unavailable to the poor Indians) and sauté briefly. Serve and eat with a dish and spoon, or eat it right out of the pan with the serving spoon. You may want to drain off a little of the liquid and replace it with cream (those poor, poor Indians) and re-heat.

Voila- the basis of a Finger Lakes regional cuisine. Admittedly, succotash still sounds like a side-dish, even with the addition of butter and cream. To make it more like a meal, add some dried or freshly fried summer squash to sweeten the mix, as the Jesuits noted in their Relations from the early 1600s. Yellow crookneck and pattypan would be the best squash varieties.

If you want more substance yet, consider frying and adding a few bits of fat meat as a garnish to the dish. Presuming that you have neither the fattier parts of bear, beaver nor deer available, a little fried-up or boiled salt pork a.k.a. side-meat or bacon would suit your purposes.

Salt and pepper would taste good on succotash, but neither would have been used in the old days. Remember that all those exploratory voyages were about discovering a new route to the spice isles to bring back peppercorns. The Iroquois got a peppery taste from adding smartweed leaves or black mustard seeds to the dish.

Salt was known in the New World but not trusted. The Onondaga regarded the salt springs in their territory as unhealthy, perhaps possessed. Instead of gathering salt from those springs, the Iroquois dried and burned coltsfoot leaves and used the salty ashes as a seasoning. To the detriment of their health, colonial settlers ignored the Indians’ warnings about the overuse of both salt and tobacco.

Waugh notes that most of the true Iroquois dishes were either some form of bread (baked or boiled) or stew (like succotash) and could have been seasoned with a “handful of gnats.” Anyone trying a first bowl of traditional Iroquois corn soup (whose ingredients are exactly the same as succotash but treated and cooked differently) would find it bland, but they are more likely to reach for the proffered salt and pepper, or sugar, than get themselves a handful of gnats, a slug of maple syrup, or coltsfoot ashes. Convenience and authenticity are often at odds, but perhaps the coltsfoot and the cream are worth a taste.

Succotash is a promising beginning, but remember that its season is less than three months. For the rest of year, a Finger Lakes cuisine would need to rely on stored foods, root crops, animal flesh (migrating birds, salmon runs), seeds, nuts and greens. Each of five or ten major seasons would have its dominant flavor, though some form of corn would appear in each. Parker says early travelers among the Iroquois were “impressed with the number of ways of preparing corn and enumerate from 20 to 40 methods.”

The Finger Lakes region was colonized by successive waves of immigrants, beginning with New Englanders moving inland, followed by English, Scots, Irish, Germans, Poles, Hungarians, Slovaks and Slovenes. The migration has never ended, though its points-of-origin have changed over time to Bosnia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, or Hong Kong. Almost all the early colonies were full of hungry people, and the mortality of colonists from hunger and Native Americans from disease was astounding. The ongoing hunger seems to prove that the Old World crops did not find a place quickly in the New World and that the colonists did not readily adopt New World foods and crops, which were all around them. It’s almost a cliché to say that the earliest colonies were saved from starvation and failure only by the intervention of the native people or food stores stolen from them.

Of course, there’s more to eating than simply having the foodstuffs available, and it must have taken some time and experimentation for the cooks to find ways to make the new foods not only palatable but delicious. To whom could they look when considering the uses of an ear of corn? The Iroquois maintained eight or ten main varieties of corn whose strengths were exploited by various means of preparation. Parker makes it clear that the Iroquois had developed elaborate methods to roast, fry, dry, re-hydrate, bake, soak, hull (treat with wood ash to make hominy), boil, grind into meal and flour, and even rot the ear of corn so as to have potentially a variety of dishes from that same ear.

*

Yesterday, I carried my lunch in a freezer bag in my backpack on a long hike along the Interloken Trail in the Finger Lakes National Forest. I stopped for lunch a mile or so on my way, sitting on a shady but dry wooden walkway, not far from the intersection with the Backbone Trail. While eating, I noticed that the boardwalk supported a colony of carpenter ants that came out to investigate the sugars they smelled in my lunch. The boardwalk was shaded by a small stand of beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), a highly edible nut when ripe later in the season, if you can beat the squirrels to them. At points on the trail, wood thrushes sang and pileated woodpeckers drummed.

I was carrying three sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper and kept cool by the cold cans of Adirondack grape soda also in the bag. Two of the sandwiches were sliced chicken, made from a thigh sautéed in a mixture of grape syrup (grape jelly which failed to set in 1994) and hot pepper flakes. Over the sliced chicken in the roll was a light slaw of chopped cabbage and broccoli stems with a grating of carrot and onion and a little vinegar dressing. There was so much failed wild grape jelly in 1994 that I’ve been devising recipes to use it ever since. The wild grapes were gathered in October from the roadsides near Hi Tor, Sunnyside and Vine Valley in Yates County. The sandwiches were made on long rolls baked by Petrillo’s of Rochester, a stronghold of Italian-Americans which, although only on the periphery of the Finger Lakes, might be honorarily included for its bread. I saved the second sandwich for a spot remembered from an earlier walk, beneath a stand of big oaks in an open field, an oasis of shade in a cow pasture.

The third roll was smeared with chunky peanut butter, non-native ingredients but crushed into a paste by the Once Again Nut Butters of Nunda, NY, an old hippy co-operative outfit. Against the organic peanut butter was absolutely fresh blackberry jam, which had been berries hanging on prickly stalks in roadside and hedgerow stands less than twenty-four hours before. Picked with some pain, carried in baskets, sorted, washed, and cooked into a deep magenta paste, gelled, sugared and preserved in glass half-pints, the berries produced surplus in the pan for a few sandwiches. The menu was a practical one, mandated by the heat of the day, need to carry and be handy to eat outdoors.

*

In its early phase, a cuisine for the Finger Lakes would need to be simple but capable of expansion and greater complexity as it comes into contact with new foods, new preparations, and other cuisines. It should be healthy, though of course anything can be taken to excess. Both succotash and grape-glazed chicken sandwiches are healthy in the sense of being well-balanced nutritionally as well as satisfying the needs of an active life. The cuisine implied here is also sustainable in the sense that we know that the crops flourish here, skilled farmers could be paid to produce these crops, some ingredients could be gathered at no cost at all, some beginning has already been made, and there is a long history behind this cuisine. These foods are affordable so they could be widely distributed and eaten in the area.

I’m not posing as a culture czar, but I will make a pitch for some foods that seem central to my enjoyment of life in the Finger Lakes. They are foods that I can grow in my garden or gather from hedgerows and roadsides, and the prospect of experimenting with their tastes is exciting. Some are literally as old as the hills; others brand new to this place. Making food that tastes good is an experiment. When I teach kids about wild poisonous and edible plants of the area, sometimes I have to explain the skill that goes into cooking. I point out that their parents don’t feed them a big spoonful of wheat flour out of the bag, but that a skilled baker can take that flour, treat it properly, add some other ingredients and produce a sweet roll. The same thing goes for wild edible plants- I give them a grape or an elderberry to sample the taste- it’s sour! Someone who knows food, like your mom, can do something with this taste. Ohhh.

Another new Finger Lakes cuisine could begin with our wines. Though grapes have been grown here for 150 years, our wines remained undistinguished until recently. Because of several amendments of New York State tax law in the early 1980s, farm land is taxed at a lower rate, and small, farm-based wineries are exempt from regulations that have hampered upstate New York’s economic development. With these modest advantages, farm-based wineries have flourished in the Finger Lakes, growing more than hundredfold in twenty-five years. Though their production is still small compared to that of the Napa Valley, these wineries have begun to produce wines of unique flavor and to attract national attention. How long it will be before the local cheeses and breads that are the proper accompaniments of these wines will be crafted by expert cheesemakers and bakers? Let me re-phrase the same question: Who will milk the sheep and goats twice a day daily? Who will get up at 3 a.m. to bake today’s fresh bread?

-by Stephen Lewandowski

A long-time York Stater, Steve has published eight books of poetry and his poems and essays have appeared in regional and national environment and literary journals and anthologies. An environmental educator, he is a founder of the Coalition for Hemlock and Canadice Lakes and has worked with numerous environmental and community organizations in the western Finger Lakes. His most recent book of poems, One Life, was published by Wood Thrush Books of Vermont. His work is either forthcoming or recently published in snowy egret, Bellowing Ark, Pegasus, Hanging Loose, Free Verse, Avocet, and Blueline.

6 comments:

Fascinating stuff. I think it's ironic that while the Onondagas were suspicious of the salt springs, Europeans were suspicious of tomatoes, a food they brought back from the New World.

'communicate information'?

Anonymous, I'm not sure what your problem with 'communicate information' is? Maybe I read something into it that is confusing to others.

Two words and a smilie: Grape Pie :)

Gee- You seem to have missed the mass movement. There IS a Finger Lakes Cuisine happening... and it is lots tastier than sucotash and wild-grape-glazed chicken. Check out Finger Lakes Culinary Bounty, or the special Finger Lakes edition of Wine Spectator (lots about the regional cuisine, too); or the articles in Gourmet, Bon Apetit, NY Times at the opening of Danos on Seneca. Or, attend the Little Lakes Festival of Wine and Food, if you prefer the Hemlock/Canadice area. I think if chefs don't imagine that there is no poetry and they have to invent it, and poets don't imagine there is no regional cuisine and they have to invent it... we could all listen happily to musicians play music, recognizing one anothers' strengths and accomplishments.

Krys-

While I agree with you that interesting developments are happening in haute cuisine, the actions of fine chefs in expensive restaurants and in the pages of Bon Apetit or Gourmet are often a world away from the food eaten by everyday folks in places like Penn Yan and Geneva. Stephen's discussion here is for the creation of a regional cuisine, one cooked in the kitchens of homes, not restaurants, that has the power to connect the people to the land around them.

I have difficulty with your assertion that we should defer to the chefs in this regard. Haute cuisine has as much power over regional cuisine as classical musicians have to campfire songs or professional poets have to nursery rhymes. Perhaps even moreso than poetry or music, cooking is a profoundly human activity and I resent the assertion that I should leave food to 'the professionals.' Until the time comes when I hire a professional chef to make all of my food, I believe that I have as much right (andy duty perhaps) to discuss food movements and the politics of food as anyone else.

-Jesse

Post a Comment