It had been a poor year for fishing, so the game warden, Ben White, could scarcely believe his eyes when Old Jack walked into the bait shop on City Pier with a string of huge fish. Old Jack had caught his limit for almost every kind of fish going. Must have been sixty pounds of fish there.

Ben said, “Well, I’ll be damned, Jack, that’s quite a catch. Haven’t seen many fish this season, but you being an old hand on the lake, you must know the right spots and what they’re feeding on.”

Old Jack said, “Yep.”

Ben asked, “I haven’t caught a fish for weeks. I’d sure like a nice bass to take home to the wife tonight. Suppose you could show me how to get one?”

Old Jack said, “Yep.”

They got into Old Jack’s boat and buzzed down the lake a couple miles. At Stony Island, Old Jack stopped, anchored the boat, then reached under his seat and pulled out a stick of dynamite. Lighting it off his cigar, he tossed it over the side. Ka-whump! Fish floated to the surface and Jack used the net to haul them in, all kinds.

Ben was flabbergasted. “I been a game warden for twenty years, and you been fishing this lake twice that. You know that ain’t legal, Jack. I’m going to have to take you in.”

Old Jack turned halfway in his seat, fished out another stick of dynamite, lit the fuse on his cigar and handed it to Ben.

“Well,” he said, “you come to fish or talk.”

***

Who Are You?

The poacher takes game outside the law. It should be clear from my name that I have no special license to use Native American materials for my own purposes in my writing, yet I do. My lineage consists of some lately arrived folks (from Poland to Chicago in 1911) and some early arrivals (from Scotland to Virgil, NY in 1800), with that scant hundred years making the difference between early and late. But what’s more important than early or late, this race or that, are the roots that I’ve put down into this place, as an individual, as part of a family that’s been in one place for two hundred years, and as part of family that knows how it feels to tear loose those roots and live as strangers.

Given a choice, I’d speak of myself as a peasant. Village people living close to the land still exist in the world; they even hang on here in America despite the erosion caused by the mechanical material culture and intrusive media. Some people might question whether it’s possible to choose to be a peasant; they ask if choice and peasantry aren’t mutually exclusive terms. However, I made my choice to live in this place, to stay close to my roots, raise my own food and cut my own wood for heat, and to pay attention to what I learn from living this way. Can I be a peasant?

Peasants were traditionally part of the land itself. When property was sold, they went along with the deal. Peasants learned early their kinship to the native flora and fauna. Owned in much the same way, trees, animals and peasants existed on sufferance as part of a lord’s domain. Peasants took game and firewood stealthily, without license or legal claim other than that of need, availability, and skill.

I approach writing as a poacher, and if caught writing without a license can only claim that the stories came to me. I look around and keep my ears open. I read landscapes, watersheds, maps and books, and poems and stories come to me from attention, study and contemplation. I know you’ve overheard someone say a poem more than once, but if you weren’t quick enough to write it down, I was.

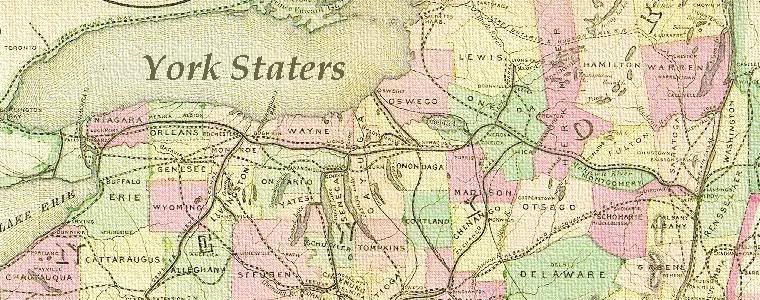

I’ve always wondered if the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) way-of-life wasn’t formed by their reading of the upstate New York landscape. I wonder, too, if by paying close attention to the same patterns and cycles, our lives wouldn’t take a shape like theirs. My writing was poached from others’ land and lives. I admit to listening. I took them, and I’m not sorry. But I didn’t take them for myself alone- here are some for you.

***

Ganondagan

Ganondagan State Historic Site is a piece of land, roughly 550 acres in extent and comprising two adjacent hilltops in the Town of Victor, at the northwest corner of Ontario County, NY. It is the only historic site in New York dedicated specifically to the interpretation of life of the aboriginal people of New York, who called themselves the Onundawaga, or People of the Great Hill, and were called by others the Seneca of the Iroquois Confederacy.

Ganondagan State Historic Site is a piece of land, roughly 550 acres in extent and comprising two adjacent hilltops in the Town of Victor, at the northwest corner of Ontario County, NY. It is the only historic site in New York dedicated specifically to the interpretation of life of the aboriginal people of New York, who called themselves the Onundawaga, or People of the Great Hill, and were called by others the Seneca of the Iroquois Confederacy.

Ganondagan was the site of a large Seneca village destroyed by a French military expedition that crossed Lake Ontario for that express purpose in 1687. Historians and archaeologists value Ganondagan for its strict provenance, as artifacts found there can be dated between its 1655 founding and its 1687 destruction.

The word Ganondagan itself denotes a place of habitation, with a reference to “the essence of white,” which some have attributed to a profusion of wild plum blossoms and others ascribe to its history in aboriginal peace-making. Ganondagan is reputed to be the burial place of the woman who first accepted the Gaiwiio, teachings translated as the Good Mind, brought by the peacemakers who founded the confederacy of groups known as Haudenosaunee, “longhouse people” or Iroquois.

The development of Ganondagan as a State Historic Site is particularly striking for the direct involvement of modern Onundawaga in its acquisition, management, and interpretation. The educational goals of Ganondagan State Historic Site are trifold: to interpret the seventeenth century life of the Onundawaga, to celebrate the peace-making impulse and its fruits, and to act as a center of modern Onundawaga culture.

Ganondagan was dedicated as a park and cultural center three hundred years to the day after its destruction by the French and their allies in July, 1687, and its Friends group numbering over 700 has provided leadership and funding for programs to bring history alive.

***

Thanks

One of the first Iroquois words you’ll hear at Ganondagan is nya:weh. You might hear some different pronunciations and see various spellings, but the meaning is always the same: thanks. When Site Manager Pete Jemison speaks the Thanksgiving Address, you hear an elaborate message of thanks. When Program Director Jeanette Miller wraps up a mailing, the committee might hear a quiet nya:weh from her.

One of the first Iroquois words you’ll hear at Ganondagan is nya:weh. You might hear some different pronunciations and see various spellings, but the meaning is always the same: thanks. When Site Manager Pete Jemison speaks the Thanksgiving Address, you hear an elaborate message of thanks. When Program Director Jeanette Miller wraps up a mailing, the committee might hear a quiet nya:weh from her.

In fact, if there is one spirit or philosophy behind Haudenosaunee culture, it is the feeling of thankfulness, at finding ourselves here, recognizing our role, and feeling the connection with the whole creation. So it should be no wonder that the Friends group that supports the site and organizes educational activities regularly expresses its thankfulness for the active support of its members, funders and volunteers. Probably it goes deeper than thankfulness as we commonly think of it because, literally, there would be no Friends group without the community’s support.

I often wonder if a more fully developed tradition of thankfulness would make a difference in mainstream American culture and suspect it would in several ways. Someone’s bound to say, ‘Well, we Christians say grace over our food,” and I’d retort just as quickly, “Yes, but what about the farmers? Do you remember them?” Nothing against the Christians and all others who ask a blessing on their food (they are about to eat it after all), but I wonder if the dinner blessing is sufficient to cover the plants and animals sacrificed to our hunger, the earth, water and sun which make growth, and the farmers who tend this part of the creation.

The Thanksgiving Address is used by the nations who make up the Haudenosaunee as an opening and closing invocation attending many rituals and observances. Listening attentively to the Address, you hear the speaker making his or her way carefully through the universe, noticing and thanking not only the Creator but the varied elements of the Creation. The Address itself is attention to these elements, and during its speaking both the speaker’s and hearer’s attention are “made one,” with one another and with the Creation. Perhaps the Address is attention in a way similar to wampum, which commemorates and records agreements and in its physical being denotes care and seriousness of purpose.

Our American culture would be changed by a greater general attitude of thankfulness. Thankfulness would slow our rate of consumption of the natural world. If we took the time to wonder, notice and appreciate where our food comes from, for example, we’d pay more attention to how it is produced, by whom, and how it tastes. Perhaps we’d eat less, and certainly we’d eat more slowly. Perhaps we’d consider hunting, gathering or gardening more of our own food.

What does it mean, anyway, that we are now mostly a nation of consumers? What happened to the producers? What is it we consume, finally, if not the Creation itself? Is there a hurry to complete this meal? All sorts of other questions could be asked here- like, is there enough for everyone?- but you are now aware of the trajectory of the inquiry, and I don’t have to ask them. You know best how the questions present themselves to you.

Let’s call the Creation by another name for a moment; let’s call it Nature, which certainly covers a lot of ground. Nature provides bountifully for us. But we consumers of Nature seem to have come to the conclusion that it would be better if we told Nature what we want, if we forced Nature to produce more and to our specifications, and if we designed Nature to serve our needs. We haven’t been shy about making our demands on Nature and seem willing to “throw away such parts” as don’t suit us at the moment.

Could we continue this rampage if we hadn’t banished thankfulness? Can we simply step aside to watch the whole roaring engine of consumption speed past, or is it necessary that we toss a branch toward the spokes of the crushing wheel?

It feels as though we are completing another annual round, and spring is poised to burst forth on a new natural year. Have you noticed that in the middle of February the cardinals, many of whom have hung around the feeders quietly all winter, begin to sing? Their song, waking us up first thing in the morning, sounds like, “Here, here, here. Birdy, birdy, birdy.” They’re singing about a fresh start: looking for mates, territory and stuff to build a nest. Once that’s done, they quiet down again.

We pause a moment to thank our friends in the Friends. Our members are strong and active. Volunteers regularly step forward to take on tasks and events, even the tough often-thankless ones, even the ones that have no clear ends, that just roll on and on, like the job of educating children. Corporations, local businesses and private foundations have helped us through the year. Despite the world’s troubles, which are many and sometimes seem never-ending, at Ganondagan we can model cooperation and understanding, true peace-keeping.

-By Stephen Lewandowski