For the past few weeks, I have been living at the Sagamore Institute of the Adirondacks in Raquette Lake. Just down-stream (three lakes away) from Raquette Lake is Blue Mountain Lake, a strikingly beautiful place overshadowed by stately Blue Mountain itself. On the slopes of this peak and at the edge of Blue Mountain Lake Village is the Adirondack Museum. I can recommend few museums more highly: it takes its self-assigned topic (the Adirondacks) and examines it from every angle possible, from art to industry, and in a thoughtful and entertaining manner.

One of my favorite exhibits within the Museum is their display of antique wooden boats. Many types are represented, but perhaps the most prominent is their collection of Adirondack Guideboats. The guideboat has, in fact, been selected as the symbol of the museum and appears embroidered into their uniform polo shirts and on their letterhead. So what is a guideboat and why is it so important to the identity of a museum dedicated to the identity of the Adirondacks?

At first glance, most of the un-initiated assume that a guideboat is a canoe since it is roughly the same size and basic shape; in other words, it is tapered at both ends. However, with closer examination, especially in comparison to an actual canoe, the guideboat’s unique qualities appear. The guideboat, you see, is a row-boat and has primarily been influenced by European boat-building traditions (with perhaps a nod to the American natives in the dual-tapered ends).

The guideboat tends to be larger by a few feet in length and considerably wider (20-30%) than a canoe. Instead of the canoe’s thworts (the beams that cross over the top of a canoe and help it to keep shape), the guideboat has a skeleton of ribs across its bottom. Like all rowboats, the operator faces the rear and pulls the oars towards herself.

There are two aspects of the boat’s creation that distinguish it: the efficiency and practicality of design to the Adirondack environment.

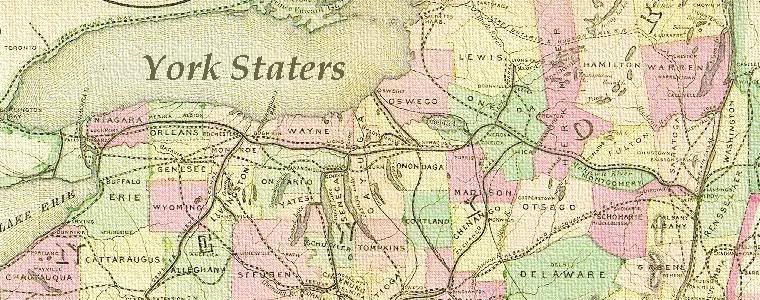

The Adirondack region is famous for its hundreds of interlocked lakes and rivers, which make a broken highway of water from the Mohawk to the Hudson or the either to the St. Lawrence. Early settlers had difficulty building roads in the swampy lowlands or the rocky highlands and instead used the waterways for transportation. However, they had problems with their typical rowboats when reaching beaver dams or rapids that needed portaging- the boat was too heavy and unwieldy.

The guideboat answers this problem through an efficiency of weight. Every possible pound is shed from her: the skin is planed down to a quarter-inch thick white pine and the spruce skeleton is chosen for her great weight-to-strength ratio. Naturally curved spruce (such as at the place where roots bend out from the trunk) is used to avoid weakening the wood through warping. No lamination, glue or cover is used beyond the pine skin itself- clinch nails are used to seal the overlapping boards into a water-tight position. In the end, what is created is a boat that one strong person can lift onto his or her back and carry for considerable distance between waterways and yet can carry a tremendous amount of weight.

The efficiency of weight and the streamlined construction of the craft have the unanticipated effect of creating an incredibly fast boat. In timed races, the Adirondack guideboat has been clocked as the fastest fixed-seat rowing craft in the world. From personal experience, I can tell you that from the first pull of the oars, a guideboat feels more like a flying bird than a boat. The ease, tranquility and speed with which it glides through the water is unmatched by any craft, wooden or synthetic, human- or motor-powered that I have ever been on.

The final aspect of the guideboat’s suitability to her native habitat is that, with the exception of screws, oarlocks and a few other small incidental pieces of hardware, all of the materials needed to create one can be found in these northern forests.

After being first invented in the mid-1800s by settlers to the region, the boat remained the “pick-up truck of the Adirondacks” for decades, used by everyone from trappers to merchants. However, she was only given her name (“guideboat”) with the arrival of tourists to the region who saw them as the province of their hunting guides. Slowly the boat became less and less of a necessary tool (especially as roads, railroads and motorized transport crept into the region) as a recreation item. Recreationists used, and loved, the boat, but did not necessarily need the weight-carrying capabilities of the craft. With the arrival of the mass-produced, cheap, canoe, guideboat creation almost became a lost art.[1] They had to be hand-made and were simply unable to compete. By the 1970s only a single elderly man was still making and repairing guideboats.

Luckily for us, and the guideboat, interest in local traditions and in the Adirondack identity surged during this time period (perhaps a response to the recently created Adirondack Park Agency and its prohibitive zoning of private land). A number of apprentices learned the craft and built shops throughout the region. One of their number, Chris Woodward, inherited the old shop and produces a single boat a year within it; he also comes down to Sagamore to teach classes (where I met him) and repairs old boats. Price tag for one new guideboat? Often over $15,000 for a hand-made, traditional boat.

It is ironic that the pick-up truck has become the Rolls-Royce, but the boats are once again slowly proliferating in the region. Yet, how many Adirondackers can afford part of their heritage? At the same time that the Adirondacks themselves are increasingly being bought off and subdivided for homes for suburbanites, the artistic heritage of the people is only available to these same outsiders. This is not only true for guideboats, but also for Adirondack packbaskets, performances of traditional Adirondack music[2], which have all become expensive for and distant from the lives of Adirondackers. Aging Adirondack artisans weave, sing and whittle for tourists up at Sagamore, and it is good there is some place for them to work, but Adirondackers drive to Wal-Mart in Utica, Glens Falls or Plattsburgh for their mittens, CDs or knick-knacks. Tourists drive a thousand miles and pay fifteen times a thousand for an Adirondack tradition and Adirondackers drive three hours for the handiwork of Bangladeshi debt-slaves from the most soulless company in America.

-Jesse

[1] It is quite ironic that these old cedar and canvas canoes have been replaced by aluminum and synthetic canoes and in the process have become rare and valuable.

[2] Which is often performed today by conservatory-trained non-Adirondackers

No comments:

Post a Comment