"The tide and time don't stand still for nobody."

Plying the Hudson in a rowboat, the young shad fisherman Everett Nack cast into the river a net he'd spent all winter mending. A few years after leaving military service, he was now self-employed, largely relying on the river for his livelihood.

He had been working for another fisherman, and decided to go out on his own.

“I worked for him for two years, and my pay was the buck shad that he didn’t want. You know, I’d bring ’em home and my mother would can some and freeze some and I’d sell a few to the neighbors. And finally I thought, "This is ridiculous," so I swapped my uncle eight muskrat skins for an old linen gill net that he was going to throw away.” (source)

This scene, Everett Nack on the waters of the Hudson, could be any time from the colonization of what is now New York State forward, though I imagine few would envision him just fifty years ago, at the beginning of a long and meaningful career and life that spanned many fields and talents, but always inextricably tied him to the river.

Everett Nack was primarily a fisherman and bait shop owner, but he was a man who dabbled in many trades, sort of a living encyclopedia of folk knowledge, de-scenting skunks, trapping muskrats, rearing raccoons, the consummate riverman. Nack and his son were some of the last commercial fishermen on the Hudson, carving out a living from fish that had for many years been in decline because of PCB contamination from General Electric factories upriver, among other polutants.

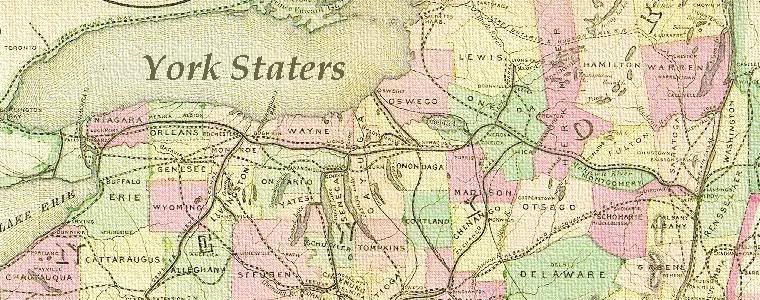

Many York Staters from further north and west of the Hudson Valley think of the area nowadays as full of commuters and weekenders from the city, an area devoid of the grizzled outdoorsmen more commonly associated with the North Country. But rare though they may be, men and women still make their living from the land and the river, and provide much more to the local community than bait.

As a man of the land and the water, Nack was as knowledgeable as any scientist about shad populations. He was hired to tag sturgeon and track fish for several studies and was an outspoken environmentalist, even talking with the governor about the condition of the river. He and his son Steven were the first to discover zebra mussels in the Hudson. He was an advocate for the river's recovery from the standpoint of an environmentalist as well as from the perspective of a working man on the river. He believed you could not be a fisherman without being an environmentalist. Skeptical but passionate, he worked the river until his death and watched its changes over half a century.

I had been living in the Hudson Valley just three years, but I had heard tell of a man who still fished the Hudson, and after an article in AboutTown, knew his name. One night in August of 2004 I was driving through Claverack when I saw on the bulletin board of the old church that Everett Nack had died. And though never having met the man and at the time knowing little about him, it was hard not to feel a sense of loss for the community and the river.

Though few of us in today's New York hold onto the old ways, we often give reverence to those who do, for they can give us a unique perspective on the economy and ecology of our state. Everett Nack was a man who loomed large in the minds of the community, and whose memory will be treasured and respected.

Posted by Natalie

1 comment:

I had the pleasure of meeting Everett Nack on a number of occasions and can say that he was truly an individual of another time and place.

Post a Comment