Every child goes through a “bug phase.” Mine far outlasted brief forays into stamps, dinosaurs, fossils, rocks and minerals, though I still have a “Herkimer diamond” from that period. In my pre-teen years, I invested heavily in baseball cards, collecting not just individual heroes like Stan the Man or favorite teams like the Dodgers but complete annual sets. I remember the thrill of trading for a Solly Hemus that completed the 1958 set.

Some would claim that my fascination and involvement with stream life clearly indicates that my bug phase endures to this day. Others, less charitable, seeing a foray with a Cub Scout Pack poking with sticks in the muddy bottom and taking the occasional soaker, would walk away muttering something about arrested development.

My bug phase was supremely unscientific. Though immersive, it had its limits. Even at its height, I was deathly afraid of spiders. Let the fearless scoff, but my autonomic nervous system would fairly shriek in the presence of a little baby spider. Of course, the worst place in the world for a person fearful of spiders is a lakeside cottage.

The porches, railings, stairs, windows and shutters of the cottage were festooned with webs to trap the gnats and flies hatching in clouds off the stream and lake. Thousands of spiders guarded and worked these meshes, especially active in the evenings when the cottage lights attracted moths and craneflies to the snares in the windows. My fear wasn’t lessened by watching spiders at work biting and wrapping their prey. I wondered how THAT would feel. Even worse, the dark corners of the cottage’s kitchen and dining room seemed to spawn huge hunting spiders whose size was augmented by the shadows. I mean, they not only inhabited the shadows but were big enough to cast their own.

My reaction to spiders was so strong that I wouldn’t willingly share the same room, car or boat with a spider. Every time we took the boat out to go fishing on the lake, there were lots of spiders under the seats, in the oarlocks and under the gunnels. Knowing what was coming, my uncles would sweep the boat out with a broom, but when a spider was found, it was a good question whether I’d stay inboard long enough for the tiny, inoffensive spider to be flipped over the side. I was very careful where I put my hands during these fishing trips.

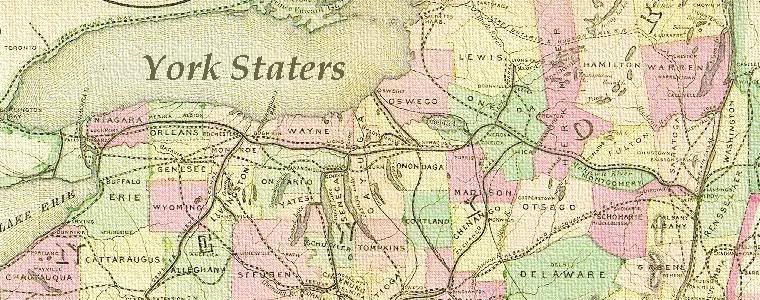

Across the creek and north along the shore, our neighbors were the Bishops. Sherman “Doc” Bishop was a gentle biologist and naturalist employed by the University of Rochester. His speciality was herpetology, and his book on the salamanders of New York originally published in the 40s has been kept in print to this day. His wife’s family had owned cottages on Canandaigua Lake for generations.

Doc Bishop died young, in his fifties, when I was four years old, but I remember him well. I don’t remember his face. Though I’ve seen many photographs of him, I don’t recognize him that way. I couldn’t pick his face out of a crowd. It was his hands I knew.

The porch railings, old wooden bridge over the creek, and dock pilings provided the large open spaces favored by the large, orb-weaving spiders late in the season. Doc was fascinated by the orb-weavers. Their intricate webs would shimmer in the early morning sun as they caught a breeze off the lake. I remember him plucking the bulbous bodies of the female spiders from their webs, like you’d pick a fruit. He would caress them with his thumb and, holding them in the palm of his hand, hold out his hand to me, to introduce us.

-by Stephen Lewandowski

1 comment:

I know exactly what you mean about spiders and lakeside cottages. My husband and I have a cottage on Black Lake in Northern NY and it is a virtual playground for those little critters. I have learned to be not so squeamish about them, but whenever we go there, the first things I do are turn on all the lights and turn down the sheets on the beds to make sure there are no "guests" hiding there!

Post a Comment